A Saunter through Kent with Pen and Pencil by Charles Igglesden (1928) - Volume 21

Contents

We have extracted the Chapters covering:-

1. Lynsted

2. Greenstreet

3. Teynham

This volume covers several other communities (not transcribed): Sheldwich, Ospringe, Wateringbury, and Yalding.

All chapters are written with a highly sympathetic eye and supported by many superb pen and ink drawings by Xavier Willis, an influential artist in the early 20th century.

LYNSTED

Summary

- Approach the village from Greenstreet.

- Pass Beaugill (then in the hands of the Selby family).

- Lynsted Village, Tudor Wall, Questionmark over "The Warrior" (now Hillside House).

- Church of Saints Peter and Paul, architectural details, including the sundial.

- Interior details of the church, some quite critical observations.

- Details of "two good brasses", Elizabeth Roper and John Worley, and some plainer brasses.

- The Roper Memorials briefly described.

- Delaune and Hugessen inscriptions - the north chapel named after Hugessen.

- Inscriptions in the War Memorial.

- Lynsted Court (or Sewards) described.

- Sunderland Farm as you leave the Village towards Sittingbourne.

- Jeffries a fine example of a yeoman's house.

- Claxfield, historic seat of the Greenstreet Family (often mistaken with the name of a road)

- Returning to Medieaval Lynsted around Ludgate Lane and Heathfield.

- Ye Olde Anchor House.

- Ludgate Farm - Malthouse - Batteries.

- Lynsted Park is discussed at length (including the lost village and manor of Bedmangore) with a brief mention of the nailbourne (underground river) that begins on the estate - the River Lyn.

HERE is a spit of God's earth where the food of man is grown, and the most luscious of food, too, and the most dainty, for here are acres, aye, miles of orchard-land and hop gardens, and cornfields in between. It is open country, standing rather high, and on every side you glimpse rows upon rows of cherry trees canopied in a veil of white when the blossom is opening to the sun. And then, later, you see the festooned strands of hop bine with the yellow bunches hanging like grapes and sending up that strange soporific odour which makes you yawn at the very pleasure of drowsiness. For the hop garden at harvest time has that sleepy effect. It is in the heart of this bit of fertile country that the little village of Lynsted lies, in itself a small cluster of buildings, and among the acres that surround it are homesteads few and far between. And what homesteads! Glorious old places built when timber was cheap.

Lynsted itself is an attractive place, uncommon as Kent villages go. For there is a tendency for most of our country streets to be on the level and to run straight; but here at Lynsted it is quite the opposite. The village stands on a slope, and the roadway bends about so as to give us numbers of surprises as we turn its corners. But what makes it the more unusual and picturesque is the tall flint wall of the churchyard standing close up against the road. Then there is the church itself peering down at us through the branches of dark green yews and other trees; opposite is a wall with lower stages of Tudor bricks to show its age, and on the other side of it an orchard; there are the two old-world houses with their dark timbers - the ancient coaching house and the vicarage - while even the hanging sign of the Lion is in unison with the rest of the picture. I shall have more to say about these houses later on.

Let us approach Lynsted from the centre of Greenstreet, the southern side of which belongs to the parish, and pass a cluster of houses. Then we go along a winding road flanked by high, green banks and on the other side of them endless orchards, and we come upon a stretch of level country given over to the growing of wheat. But even here you get glimpses of cherry trees - you can't get away from them, those rows upon rows of trees of perfect pruning that make this bit of country, as dear old Lambarde said, " the cherry garden " of England.

A few yards beyond we burst upon a few houses, sentinelled by a great sombre yew, whose branches hang over the highway. One house is thatched but modernised by the insertion of plain wooden windows, the old ones and a doorway having been blocked up. Almost adjoining is a larger house, also of brick, which at one time possessed an impressive doorway, but most of it has been blocked up and entrance is effected through a plain deal door. The doorway itself is of ornamental design, and in the space under the arch is the date 1675 and the lettering " B.A.H." As the filling in this space is apparently of later date than the rest of the doorway, the house itself probably dates back further than 1675. A stringcourse runs around the house and rises gracefully over the arch of the doorway. In this house, too, old windows have been blocked up.

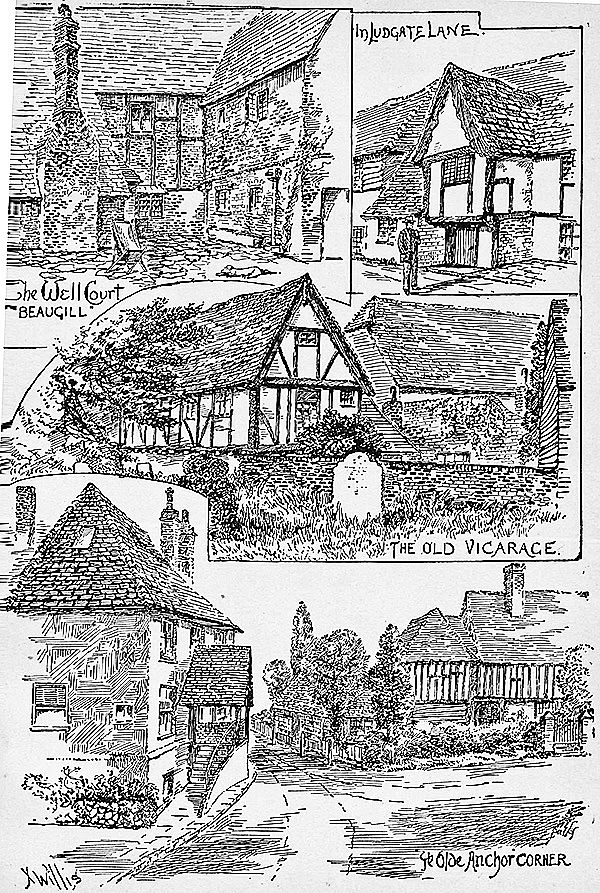

It is on the opposite side of the way that a beautiful specimen of a mixed Tudor and Jacobean house stands - Beaugill, now the property of Dr. Selby, after passing through the hands of the Drurys, Hugessens and Barlings. Today the feature of this long red-brick house, with a timbered frame still showing, is the prominent porch, bricked like the rest of the building but with a delicate barge-board in the gable, in the centre of which are the date 1643 and the letters " H.W.I.I." The first stands for Hugessen, the second for William, the third for John and the fourth for James or Josias, for these two names were borne by members of the Hugessen family. There is but little doubt that Beaugill was originally a Tudor house, square and with thatched roof. It was then the property of the Drurys, from whom James Hugessen bought it. The Drury mansion opposite the church was pulled down in 1643 an(^ the material used in adding to Beaugill in the seventeenth century. We thus have two distinct periods represented, the Tudor bricks having been used when a wing was added on either side. Of a mellow tint, these bricks, many of them in herringbone design, give the house its distinctive character. At the back is the original well court, a quaint corner from which water can still be drawn. With careful study of domestic architecture Dr. Selby has not only restored the house which, when he purchased it, had been converted into four tenements, but the surrounding garden breathes the old-world atmosphere. Inside we find a mass of heavy timber, most of it in situ, while that which has been added is equally old and brought from the buildings in the neighbourhood. The cross-beams supporting the hall roof are of chestnut, with the reddish tint that gives this wood a delightfully warm effect. The doorway that gives entrance from the porch is a fine Tudor specimen, but a second door leading out of the hall is remarkably ornamented something in the style of the linen-fold pattern. The old door latches and metal hinges and window catches are still in use, and in the latticed windows can be seen some of the famous green glass of many years ago.

Wherever you ramble in Lynsted you come across delightful specimens of the timbered house style of architecture, but just outside the village street stand the yellow-brick schools, a fine block of buildings erected in 1877. At the neighbouring corner is an old house, partly timber framed and partly of brick. The beams that support the upper storey project and show signs of having weathered rough times, while the uprights bear evidence of similar ill-usage from the pitiless rain. Nearly opposite is the Lion, with its two front gables and standing flush with the roadway, minus any steps - those steps which are so well worn outside many a hostelry and a danger zone at times to the habitués leaving as the clock strikes ten! Lower down the road are the remnants of a Tudor wall, to which I have already referred. Here stood the mansion of Sir Drue Drury, a knight who married a daughter of the previous owner, William Finch, and was Gentleman Usher to the Privy Chamber of Queen Elizabeth. His son demolished the house built by his father, and the material was used in enlarging Beaugill. On the same side of the road is a house to which access is obtained by steps leading to the front door, and overhead is a stone plaque containing the head of a warrior. I was told by a native that this building was once a public-house known as The Warrior. Hence the head over the doorway. A likely story, perhaps, but in this case only a story, for, as a matter of fact, the bit of carving came from Lynsted Park, previously known as Lodge, Lynsted, when that mansion was partly demolished in circumstances to which I shall refer later on.

And now we mount the pathway leading to the church, the position of which gives character to the village, for, standing on an eminence, it looks clown upon the winding street below. The road is cut off from the churchyard by a tall flint wall - what time must have been occupied in preparing those hard flints! - and within it are six fine yews, brought from Eastling and planted here two hundred years ago. The wall encloses the churchyard on three sides, but you get a glimpse of a picturesque old timbered vicarage through the trees, and a hop garden stretches away in another direction.

The church itself, named after St. Peter and St. Paul, is a building in a state of good preservation and consists of a nave with two aisles, a chancel, two chapels, a south porch and a tower placed in the north-west corner. The polished flint work is very fine. A glance at the exterior shows that the whole structure is in the Decorated and Perpendicular styles so common in this part of Kent. The tower is conspicuous, being square and of a considerable size, with large corner buttresses, and surmounted by a wooden construction with a shingled spire. There are three string courses with lancets between. A stroll round the building brings us to a pretentious porch, while a second building similar in size and style is the chapel of the Teynhams. In the wall are two niches, as well as a stone recording the deaths of several members of the Teynham family.

A priest's doorway is in the north; the west doorway is rough in character and the hood has almost disappeared. There are several original windows, but on the other hand others have been restored and consist practically of new work. When you reach the west corner by the tower there is evidence of great alterations in early days, and among other things is a blocked doorway.

The porch is built of flint and over the entrance is a sundial with the words :—

EVERY MOMENT WELL IMPROVED

SECURES AN AGE IN HEAVEN.

The ceiling is coved and the interior was once lighted by a small window, but this has been filled in. On a stone quoin of the doorway is a scratch-dial.

Entering the church you find it well lighted, the nave roof being of good pitch, ceiled and carried on tie-beams with slender king-posts. The chancel is very large and its extent is intensified by the absence of shafts to the chancel arch. It is all very open. The two aisles are divided from the nave by arcades with expansive arches, three in the south and two in the north, one of them in the latter position being taken up with the tower. All the arches have octagonal piers and capitals, but the one on the eastern side of the south arcade dies into the wall. There are other fine arches dividing the chancel from the two chapels, and also between the aisles and chapels; the chancel arch is particularly wide and lofty, and springs direct from the wall. The tower is entered by two doorways, one opening from the aisle and the other from the nave.

A feature of the church is the rood stair turret. It is lighted by slits in the outer walls, and both doorways, as well as the steps, are in a perfect state of preservation. Other features consist of a small niche below one of the windows in the north aisle; a new font, octagonal in shape, with sunken panels, but with an ancient cover richly carved, and the steps of an altar which once stood in the south chapel. Until quite recently the interior was spoilt by an ugly gallery across the west end, in which was a small organ. There was also an unsightly dormer window in the roof of the south aisle, but this has fortunately disappeared.

There are two good brasses. One represents Elizabeth, widow of John Roper, a lady who, according to the inscription, "ledd her lyfe most vertuously and ended the same most catholykely." No date is attached, but she is supposed to have died in 1561. The figure is clothed in a French hood, ruff and gown, with a petticoat of delicately designed embroidery. The small effigies of her son and two daughters are attached, as well as shields. The second brass states that the bodies of John Worley and his wife, of Skuddington, Tong, lie beneath. They are represented standing side by side, he in civil dress in a cloak, with a sword, she in a calash, ruff and gown. The date of his death is given as 1621, but the space left for the date of his widow's death was never filled in. Two plain brasses with inscriptions are connected with James Hugessen, late of Dover, merchant, who died in 1637, and Elizabeth, widow of William Hugessen, her death occurring in 1642, A modern brass has been placed under the chancel arch to the memory of Philip Barling and his wife. They lived at Nouds; she died in 1881 and he in 1897.

Coming to the windows we find the large coloured one in the Perpendicular style over the altar erected by the Rev. John Hamilton to the memory of his daughter who died in India in 1871. There are several windows of the Decorated period or fourteenth-century, but one, in the south chapel, is blocked up. A stained-glass window in this chapel was erected to the memory of his departed ancestors in the adjoining mausoleum by Charles Henry Tyler in 1855. In the north chapel are two three-light Perpendicular, or fifteenth-century, windows. One is plain and the other contains stained glass to the memory of Fanny Catharine Knatchbull, who died in 1882. Other coloured windows are in the north aisle - Decorated one of two-lights to the wife of Charles Murton, of The Batteries, who died in 1870, and the other, of three-lights and of the Perpendicular period, to the Rev. John Hamilton, who was fifty-two years vicar and died in 1891 at the age of eighty-four. In the twin chamber of the tower, now used as a vestry, is a deeply-splayed lancet, and another feature is the fine old door that leads into this room.

Although the Ropers took their title from the neighbouring village of Teynham, their principal residence was at Lynsted, and in the church of St. Peter and St. Paul many members of the family are buried, while some of their beautiful monuments adorn the south chapel. By the south wall is a large marble monument with two recumbent figures in the centre, the man being in armour and the woman in skirt and ruffles. At the back are the kneeling figures of their two up-grown children, the son in armour and the daughter in a costume similar to the one worn by her mother. All the figures are coloured in places. Corinthian columns and a brilliant coat-of-arms add to the effect of the tomb. This is the monument of the first Lord Teynham, who died in 1618 at the age of eighty-four and who was buried there in a vault below made by him. His wife was also buried there, she having died before he received the title. The family name of the Lords Teynham was Roper, a family well-known in Kent and who owned big estates in this district, while during the reign of Henry the Third they flourished at Appledore. It was one John Roper, of Badmangore, who was rewarded for his loyalty to King James the First, having been the first man of note to proclaim that monarch King in the county of Kent, He was knighted and created a peer on the same day, July 9th, 1616. His successors made no mark in public affairs, although the fourth baron was lord-lieutenant of Kent in 1687. Many died young and others remained unmarried, and since the creation of the title just over three hundred years ago there have been no less than twelve Lord Teynhams. They resided at Lodge, Lynsted, now known as Lynsted Park.

The second monument in this chapel is remarkable for the position of one of the effigies. Lying down is the figure of a man in armour with a cloak thrown about him and a lion at his feet, but his wife, instead of being" at his side, is kneeling1 under the arch of the tomb - a woman kneeling- before an open book on a reading- desk, and dressed in black. The figures of their children, a son and two daughters, are below. Corinthian columns support the tomb, which is coloured here and there. This is the tomb of Christopher, the second Lord Teynham, who died in 1622, and it was erected by his widow.

[Society Note: You can read a very detailed account of the Roper memorials by Aymers Vallance, written in 1932.]

In the south wall of the south chapel is an ornate marble and gilt monument to the memory of members of the Delaune family, who were related to the Hugessens.

In the north, or Hugessen, chapel is a large collection of monuments, the majority attached to the walls. But at the east end is one containing- two recumbent figures, the man being- dressed in rich civilian costume, while the woman is also garbed in the style of the seventeenth century. In a recess at the back are the small kneeling- figures of their seven children. Corinthian columns support the canopy and the whole of the monument is coloured. The inscription is as follows :—

"TO THE MEMORY OF JAMES HUGESSEN, ESQ.,

MERCHANT ADVENTURER, HE DECEASED THE 2

DAY OF OCTOR ANO 1646. AND TO YE MEMORY

OF JANE HIS WIFE BY WHOM HE HAD ISSUE,

WILLIAM, JOHN, JAMES, JOSIAS, PETER, WALTER,

AND MARY. WILLIAM HAD TWO WIVES, VIZ.

ELIZABETH DAUGHTER OF ,SR JOHN HIPISLYE

KNIGHT, THE SECOND WAS MARGERY, DAUGHTER

TO SR WILLIAM BROCKMAN KNIGHT, AND

MARY THE DAUGHTER WAS MARRIED TO ROBERT

EVERINGE ESQ., HEYRE OF EVERINGE.

INFANCY, YOUTH, AND AGE ARE FROM YE WOMBE,

MAN'S SHORT BUT DANGEROUS PASSAGE TO HIS TOMBE,

HERE LANDED (THE PROCEEDS OF THAT WE VENTURED)

IN NATURE'S CUSTOM HOUSE THIS DUST IS ENT'RED.

CHRIST'S ALL OUR GAINE BY WHOM IN DEATH WE LIVE,

AND CARRY HENCE THAT ONLY WHICH WE GIVE,

ALMES DEEDES ARE SECRET BILLS AT SIGHT (THE REST

ON HEAVEN'S EXCHANGE ARE SUBJECT TO PROTEST).

THIS UNCORRUPT MANNA OF THE LUST,

IS LASTING STORE EXEMPT FROM WORMS AND DUST."

There is in this chapel a plain black marble monument that bears this inscription :—

" HERE LIETH YE BODY OF JOSIAS HUGESSEN,

GENT., THE 4th SONNE OF JAMES HUGESSEN,

ESQ., AND OF JANE, HIS WIFE, WHO MARRIED

MARY, YE DAUGHTER OF MR. AMBROSE ROSE,

YE PISH OF CHESLET, IN THIS COUNTY, BY

WHOME HE HAD ONE ONELY DAUGHTER, NAMED

JANE, OBIT. 20 NQVEMB., AO. DNI. 1639, AETAT SUOE 22."

The Hugessen family is well-known in East Kent and they inter-married with the Knatchbulls. We first read about the Lynsted branch during - the reign of Charles the First, when James Hugessen, described as a " Merchant Adventurer of Dover," purchased the residence, Sewards, from Sir Drue Drury. He died in 1646, being-succeeded by his son William, who pulled down the old residence and went to live at Provender. It was a daughter of William Western Hugessen who married Edward Knatchbull.

In the corner of the north wall is a marble monument representing-the two figures of a man and a woman kneeling at a fold stool, while beneath is seated a child clad in a gown of ermine. The inscription is :—

" RETURNED TO EARTH AGAINE HERE MAY YOU FIND

THE CORPS THAT LIVING LODG'D AN HEAVENLY MIND,

AS FROM HIS CHILDHOOD UNTO MAN HE GREW,

DUTY TO GOD AND MAN GREW IN HIM TOO

WITH KNOWLEDGE HE RESPECTED EACH DEGREE

AND WITH HIS KNOWLEDGE MIXED HUMILITIE

WHEN HE WAS COME TO YEARRS AT WCH ARE HURLED

MENS WARDSHIPS OF, HE THEN CAST OFF YE WORLD

TO FLY TO HIS INHERITANCE ABOVE,

" UPON THE WINGS OF FAYTH AND GODLY LOVE.

SOE DID HE LIVE AND DYE IN PERFECT TRUST

TO RISE AGAINE AND LIVE AMONG THE JUST."

There is yet another monument touched up with gilt and representing- a man and woman kneeling-. He is in armour and she in the dress of a lady of the sixteenth century. Behind him kneels his son and behind her are her three daughters. The inscription is: "Here lyeth Dame Catharine, late wife of Sir Drue Drury, Kt., Usher of the Privy Chamber of Queen Elizabeth, daughter and sole heir of William Finch, died 1601."

One tomb has the following- inscription :—

NOW DRY YOUR TEARES AND KNOW THEY MUST NEVER DY,

THAT TO THE WORLD CAN LEAVE A MEMORY,

LIKE THIS YOUNG MAN WHO FROM HIS CHILDHOOD GREW,

UP TOWARDS HEAVEN TQ GOD IN SERVICE TRUE,

TO PARENTS DUTY TO SUPERIOURS STILL

IN FITT OBSERVANCE, TO ALL MEN GOOD WILL,

AND AT HIS END GAVE OTHERS LIGHT TO SEE

THE READY WAY TO BLEST AETERNETIE."

On a slab in the chancel is the following remarkable inscription :— "To the memory of Dorothy, wife of Charles Eve, of Canterbury."

" HERE LODGE THE RELICKS OF A VIRTUOUS WIFE,

WHOSE SICKLY FRAME EMBITTE'D ALL HER LIFE,

TO HER, GAY SMILING HEALTH DEYN'D HER AID,

AWHILE SHE VISITED, BUT SELDOM STAID.

DEATH, SUDDEN DEATH AT LENGTH AFFORDED EASE,

AND CROPT HER IN THE BLOSSOM OF HER DAYS,

ALAS TOO INSTANTLY TOO SOON REMOV'D

FROM HIM SHE HONOUR'D AND FROM HIM SHE LOV'D

THIS TOMB (TWAS ALL HE COULD) THE HUSBAND GAVE,

AND PAID THIS MOURNFULL TRIBUTE TO HER GRAVE."

Several mural tablets hang on the walls. One is to the memory of Thomas Barling, "descended from the Barlings (otherwise Barrnalings), of Egerton," He died at Lynsted in 1770, and the inscription says: "To say anything of his character, temper and good principles is unnecessary, as he lived 40 years in this parish." The tablet was also erected to the memory of his two wives. Another is to John Barling, of Nouds, who died in 1853, as well as his wife; and yet a third is to another member of this family, John Smith Barling, " impropriator of this parish," who died in 1795. An impropriator is a layman in possession of church lands or holding the presentation of a living. There is a marble tablet to the memory of John Hunt, who for forty years "conducted an extensive and respectable Academy in this parish." He died in 1829, and mention is made, of his two sons, who died just before him from consumption. One was curate of Luddenham and Teynham. Another tablet is to the memory of Samuel Creed Fairman, who died in 1858.

I have already mentioned the impressive monument erected to the Teynham and Hugessen families, but there are tablets also. One is to the Hon. Betty Maria Tyler, who died in 1788; another to Kate, wife of Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Roper Tyler; one to Lieutenant-Colonel John Roper Tyler, of the 80th Regiment and sometime of The Buffs, who died in 1914; to Colonel Charles Henry Tyler, of the East Kent Regiment, who died in 1872, and his wife, who died four years later; and to the Right Hon. Lord Teynham, who died in 1821. The Hugessen tablets include one to William Western Hugessen, "who was happy in the form both of his body and his mind. He was naturally modest, gentle and polite, which a liberal education had duly improved." He died in 1764, and his widow, " very sensible of her loss and his merit, dedicated this monument out of a pious regard to his memory." Another tablet is to the Right Hon. Sir Edward Knatchbull, Bart., who died in 1849, and his widow, Dame Fanny Catherine, who died in 1882. There is a tablet to Anne Delaune, widow, daughter of Sir William Hugessen, first married to Rodolph Weekerlen, then to Gideon Delaune, " to both a most loving and dutifull wife, shee was exemplary, pious towards God, charitable to the poor, just and usefull and agreeable to all and being full days and good works shee departed life 1719." A later tablet records the death of Herbert Thomas Knatchbull-Hugessen, who was M.P. for the 'Faversham Division of Kent from 1885 to 1895. He died in 1922.

In the the tower are five bells. The two oldest are dated 1597 and 1600 and inscribed: " Robertus Mot me Fecit." Two others were made by John Wilnar in 1639 and the remaining one was recast in 1884, it having always given trouble as an inferior bit of workmanship by Robert Mot.

The marble War Memorial on the wall bears the following list of names, very long for the size of Lynsted: —Leon Lorden Ackerman, Charles Peter Booker, Amos John Brown, Frederick Percy Carlton, Henry Thomas Carrier, Robert Stewart Clark, Stanley Monkton Cleaver, Malcolm Philip Dalton, MacDonald Dixon, William Charles Dray son, James French, Reginald French, Herbert David Gambell, Wilfred John Gambell, William Gambrill, Reginald Frank Gilbert, Frederick Godfrey, Albert Edward Hadlow, Charlie Hollands, Frederick Thomas Hollands, Arthur Hughes, Edward Jordan, Herbert Ewart Kadwill, Ernest Cecil Kemp, George Lombardy, William Henry Packham, Thomas Quaife, John George Lorett Sattin, William Allan Sewell, Elvy Thomas Sims, Frederick Percy Smith, Alfred Charles Tolhurst, Sydney Arthur Watts, Reginald Douglas Weaver, Frederick Walter Wiles,

Not far from the church, and standing back from the road amid cherry orchards, stands historical Sewards, a choice specimen of the timber-framed style of architecture of the Elizabethan period. Some time since the original name was dropped and it is now known as Lynsted Court. Here was the ancient seat of a family of the name of Sewards, but during the reign of Henry the Eighth it came into the hands of the 'Finches through marriage. These Finches were ancestors of the Earls of Winchelsea and Nottingham who subsequently owned Eastwell. During the reign of Queen Elizabeth, however, it became the (property of Sir Drue Drury, whose connection with Lynsted I have already mentioned. Later on it was owned by Mr. John Smith Barling, of Faversham, but now belongs to Mr. Norman Smith, who resides there.

When you first get a glimpse of the house through the trees it presents a charming appearance, and upon closer examination you are not disappointed in the building, for it makes an exquisite setting to a mediaeval picture. It is one of those houses in which the entrance to the large hall was from one of the corners instead of the centre, and here was a delightful porch with a chamber above. On each wing is a fine gable, and under the barge-board of one of them some extremely delicate open carving, while on the gable at the other side the ornamentation is of a bolder pattern. This second gable is almost unique for under the large gable is built a smaller one in perfect proportion. The overhang of this wing extends along both front and side, and the old timber frame is supported by a massive wall of flint and bricks. The outer beams of the entire building are of the needle pattern, extending from the roof to the ground.

Unfortunately, the interior was by previous owners despoiled of some of its beautiful doors and other elegant woodwork, but the beams that remain are evidence of the massive nature of the structure. In one room is a fine stone Tudor fireplace, recently rescued, plaster having been used at one time to cover in the arch, while a modern stove hid the open fireplace. At one time, too, there was a fresco on the walls of this room in panel design, but most of this has been scraped away and only a small portion remains. The plaster ceiling, however is fortunately intact and is of an octagonal pattern. A peculiarity of the house is the heavy beams upon which the rest of the structure is supported, and these beams act as a skirting to the rooms. In two small windows the original glass in the leadlights can be seen.

Further afield in the parish of Lynsted we come across many other old houses of Elizabethan days. If you follow the road out of the village towards Sittingbourne, at one of its bends you get a glimpse of timber work filled with white plaster, but the other corner of the house, built of red brick, is deceiving. Turning the bend, however, the front of the house bursts upon you and arouses admiration, for here is another of those timber-framed houses built in Tudor times. It is long and flat-fronted, with the ends of the first storey beam protruding, while roughly-hewn and solid corner posts remain. Modern windows, however, have given place to the old lead-lights, while some smaller windows close under the eaves have been entirely blocked up. Fortunately, the original oak doorway remains, and in the spandrels are carved Tudor roses. A fireplace in one of the rooms bears the date 1657. This is Sunderland Farm and belongs to Mr. Mercer. In early days it was known as Sundrise or Sundries.

Following this same road you come to an even finer specimen of the black-and-white yeoman's house now known as Jeffries, so named after a one-time owner of the place. Here we find a very deep overhang, but a large corner-post in the centre shows that one side/ of the building is older than the other, and that here in the centre was the outer wall of the earlier part. Within the house are good fluted beams, while some of the heavier baulks of wood are ship's timber, probably brought from vessels either wrecked or broken up in the Swale, which flows a short distance away. The floors are of oak, and upstairs is a fine old panelled door. The ceilings are ancient. Two of the original lead-light windows remain. A peculiarity of Jeffries is that the timber frame of which the house is constructed was placed on foundations of flint. It is now the property of Mr. Terry Hadlow.

Still further along this road, and within a stone's throw of the great highway between Greenstreet and Sittingbourne, is Claxfield, which was the residence of the famous family of Greenstreet, who possessed many big estates in this part of the county for several generations, and some of whom lie in the parish church of Lynsted. Passing put of the hands of the Greenstreets, it became the property of the Sawbridges, of Olantigh, near Wye, but it now belongs to Mr. Potter Oyler and has been divided up into two tenements. It can be truly said that it possesses one of the most beautiful fronts ever built during the time of Elizabeth. The timber frame is filled in with white plaster, and a beautiful porch is its principal feature, and the whole place must have looked exceedingly picturesque when the old lead-light windows existed. Unfortunately, modern window frames have been inserted. Over the porch is what was known as the powder room, in which the ladies powdered their hair in mediaeval times.

I have already referred to the wealth of Lynsted in the number of houses dating back to the Tudor period - those fine buildings that stand out in prominence whether in the meadows or by the roadway, owing to the very distinct contrast of their dark timbers and light filling of white or ochre-tinted plaster. Here in the very heart of Lynsted are three of them, and if you stand where Ludgate Lane joins the main road you feel that you are gazing at a mediaeval village. To be exact, you are looking at buildings that stood there by the side of the church at least four hundred years ago.

Heathfield is the house closest to the church and belongs to Mr. Smith. The part of it which faces the street and Ludgate Lane has been covered with weather-boarding, but on another side the fine timbers are open to view. Here the barge-board of a gable is ornamented to represent a scroll and the Tudor rose. Originally you went down two steps to reach the floor, but alterations have been made since then. Partitions have also altered the interior, but two remarkable doorways are to be found upstairs, made of the thickest timber I have ever seen in the upper storey of a Tudor house. No planes were used either on these doorways or on the extremely massive beams all over the house; the mark of the adze is only to be seen. Supporting one beam is a bracket on which is carved the date 1580. The huge beam over an old chimney corner has been covered in, with the exception of a carved panel in the centre, containing the uncommon design of a Tudor rose with four leaves.

Just across the road is a very fine specimen of a Tudor house, the filling between its timber frame being of a warm ochre colour. Today it is cut up into two tenements, but once upon a time it was a famous coaching house known as Ye Olde Anchor. Judging from the timber, one part—the western side—is of the very early Tudor period, probably of the time of Henry the Seventh; the other end is a trifle later. A few years ago a part of it was consumed by fire, but the father of the present owner, Mr. Norman Smith, cleverly rebuilt the corner in brick and left much of the timber. What superb baulks of oak must have been used in the original building of the place, for although this part of the house was hopelessly gutted most of the timber withstood the heat and the flames and stands there to-day apparently uninjured! It is difficult to define the actual structure as originally built, but, notwithstanding the erection of partitions and floors, it is evident that the central hall extended from floor to roof, in which the cross-beams and king-post can still be seen. The doorway contains a strange mixture of woodwork, including Tudor work with crenulated ornamentation overhead. The long, low window facing the church is remarkable through being made of thick pieces of wood representing stone and painted in stone colour. The result is cleverly deceiving. Within the original bar parlour are two stone brackets upon which thirsty souls were wont to place their tankards of ale.

Just across the road is a very fine specimen of a Tudor house, the filling between its timber frame being of a warm ochre colour. Today it is cut up into two tenements, but once upon a time it was a famous coaching house known as Ye Olde Anchor. Judging from the timber, one part—the western side—is of the very early Tudor period, probably of the time of Henry the Seventh; the other end is a trifle later. A few years ago a part of it was consumed by fire, but the father of the present owner, Mr. Norman Smith, cleverly rebuilt the corner in brick and left much of the timber. What superb baulks of oak must have been used in the original building of the place, for although this part of the house was hopelessly gutted most of the timber withstood the heat and the flames and stands there to-day apparently uninjured! It is difficult to define the actual structure as originally built, but, notwithstanding the erection of partitions and floors, it is evident that the central hall extended from floor to roof, in which the cross-beams and king-post can still be seen. The doorway contains a strange mixture of woodwork, including Tudor work with crenulated ornamentation overhead. The long, low window facing the church is remarkable through being made of thick pieces of wood representing stone and painted in stone colour. The result is cleverly deceiving. Within the original bar parlour are two stone brackets upon which thirsty souls were wont to place their tankards of ale.

As you start to stroll along Ludgate Lane you are struck with admiration of a quaint little black-and-white house, with timbers so shrunken that its porch has become very uneven. This square porch, projecting into the roadway, is the special feature of the house, the floor of which is approached by downward steps—evidence that the road has been raised in recent times. By following this lane you pass through a wealth of orchard land and reach Ludgate Farm, standing on the crest of a slope. This homestead is another specimen of the timbered house of the Tudor period.

A conspicuous house is Malthouse, a residence perched up on a slight eminence along a road leading out of Greenstreet. Here is another of those old picturesque buildings which have stood the ravages of weather, its blackened timbers showing strength that will last for centuries. These timbers have twisted out of the perpendicular in places, but only to settle down into a position of solidity. The gabled porch, the feature of the house, is slightly lop-sided. Modern windows have replaced the old, but two of the original remain; and there is a fine Tudor doorway. The owner of Malthouse is Mr. Potter Oyler.

top

Another ancient black-and-white house was Batteries, originally known as The Batteries. No one can tell me how it acquired such a warlike name while resting in such a peaceful spot of God's earth, although one resident suggested that a family by the name of Batt once lived there. Some fifty years ago a Mr. Murton pulled down nearly all the old building, leaving only some remnants at the back, and here a massive beam can be seen. The property now belongs to Mr. Montague Mercer.

You have to go some distance on the road towards Doddington before you come to the famous seat of the Ropers who subsequently became peers of the realm. It is recorded that in 1627 they owned no less than twenty extensive manors in Kent. What remains of the land at Lynsted is now known as Lynsted Park, but at one time it went under the name of Lodge, and the estate comprised the manors of Bedmangore, Lodge, Teynham and Newnham. Hasted spells what is now known as Bedmangore with an "a"—Badmangore. We have to go very far back into the centuries when tracing the history of this place, back as far as the Cheneys and the Apulderfields. It was a member of the former family, Sir Alexander de Cheney, who was knighted for bravery at the siege of Carlavelock by King Edward the First, and it was his son William who possessed Bedmangore. The property eventually came into the hands of Sir John Fineux, lord chief justice during the reigns of Henry the Seventh and Henry the Eighth, through his marriage with Elizabeth, heiress of the Apulderfields, an ancient and eminent family in Kent. Sir John 'Fineux's daughter, Jane, married John Roper, Attorney-General, in the reign of Henry the Eighth, and brought the property into the Roper family. Lynsted Park is now owned by Mrs. Roper-Lumley-Holland, who resides there with her husband and mother. She is a descendant of the Apulderfield and Roper families, and is Lady of the Manors of Bedmangore, Lodge, Newnham and Teynham.

Some delightful grounds now surround the residence, the portion of the park nearest the Toll Wood being picturesque and undulating, and remarkably fine trees of various sorts rise majestically out of the lawns. Here you admire a tall ash, a cedar of Lebanon, chestnuts and, most impressive of all, three huge Italian cypresses, fifty feet in height and some three hundred years old. Some distance from the house is to be seen a clump of chestnuts, one of which is twenty-seven feet in circumference, and these trees are planted as though intended to surround a bowling green similar to the one that can be seen at Penshurst. The house and gardens are surrounded by four roads, and close to one of them is the site of the original residence.

Here was the village of Bedmangore. Details regarding the ancient manor house at Bedmangore are not known. But it is recorded that in 1599 the first Lord Teynham, possibly owing to scarcity of water, removed from one site to the other, about a quarter of a mile away, where abundance of water was available, and here he erected a fine mansion, a portion of which still remains. There were six courtyards, and the foundations of the original house and courtyards can still be traced. From the site of the ancient building at Bedmangore to the one erected in 1599 a coach drive was made, and planted with an avenue of limes. These fine old trees, very symmetrical in shape, form an approach to the present house. One of the old entrances with a postern gate at its side can be seen today in the Lion's Court, about three-quarters of the way up the avenue. In the south walled-in garden can be seen another entrance with a postern gate in excellent preservation. In the garden, too, is a well now opened to the sky, but at one time within the mansion. There was also a private chapel, below which is a large building said to be a crypt. The chapel has disappeared, but the crypt remains and the original entrance from the house has recently been opened up. It was never used as a burying place, as the mausoleum adjoins the family chapel in Lynsted church. Such a building as the crypt must have been useful as a place of refuge in troublous times, especially during the Civil Wars.

A wing was added to each side of the Elizabethan mansion by Ann, Baroness Dacre in her own right, wife of the eighth Baron Teynham, a lord-in-waiting to George the First. The mansion was three storeys high and contained a hundred rooms, and must have been very expensive to keep up. It is not surprising that the wings and a large portion of the extensive buildings were pulled down about 1829. The central portion, red brick, since covered with rough cast, was left, and forms the present house. In recent years an entrance has been made at the west front, but the beautiful Tudor porch still remains at the east side of the original frontage. It is coloured in black and white, and is more ornate than most porches of the sixteenth century. The Tudor doorway is typical of the period. Above the porch is a chamber possibly used as a powder room, although it was customary for the ladies to select a place without windows, so that the powder with which they adorned their hair should not be blown about. Facing the porch is a circular lily pool and fountain, with the original stonework, recently discovered during excavations.

The interior contains many features that recall Elizabethan days. The best of all is a staircase with a balustrade of delicate design, clusters of leaves standing out singly from a hollow centre. There is also a Tudor archway of oak in the hall. In two oak-panelled rooms are fine plastered ceilings. One has an interlaced design with medallions containing the faces of historic personages, and the initials of John Roper-J.R.-can be seen on the ceiling, while the Other - known as the Arms Room-bears the date 1599 on the ceiling, which has deep bosses, and here again are more medallions and the coat-of-arms of the Roper or Teynham family, as well as a fine frieze. The oak fireplace has carved human heads on the top of pilasters. The large bay window looks out on a sunken garden, and the ancient Italian cypress trees give a distinctive feature to the lawn. From the valley near by the River Lyn flowed centuries ago, but long since it dried up.

Family portraits dating from the time of Henry the Eighth to Mrs. Roper-Lumley-Holland hang on the walls of the rooms, noticeable among them being one of John Roper, whose son William married Margaret, the devoted daughter of Sir Thomas More. It is said that the head of the celebrated Lord Chancellor was buried with his daughter in the old Roper vaunt in St. Dunstan's Church, Canterbury. The number of interesting pictures include a quaint painting on panel of Sir John Fineux, a panel of Henry Nevill, Lord Abergavenny, dated 1586, and also numerous portraits of the Roper and Dacre families.

It is recorded by Hasted that " a large chestnut tree was felled in Lodge Park, which was sawed off close to the ground; in the centre of it, where the saw crossed, was a cavity of about two inches diameter, in which was a live toad, which filled that place entirely. The wood of the tree was, to all appearance, perfectly sound all round it, without even the smallest aperture whatever. The tree itself was six feet in circumference."

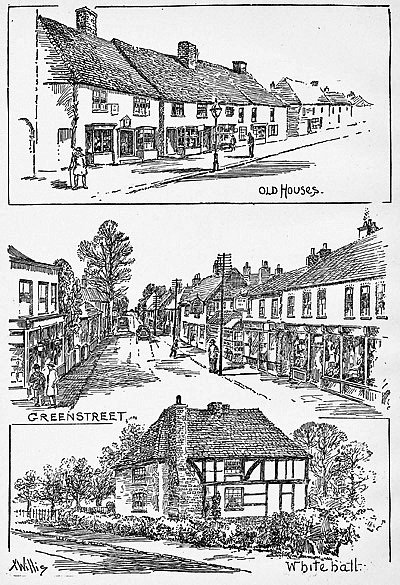

GREENSTREET

THE traveller when passing through Greenstreet will be led to think that it lies in a country far from picturesque. Certainly it is a long, closely-packed street, possessing buildings neither fronted with bright gardens nor sheltered by spreading trees. No; this is not quite fair, for I noticed one tall tree growing alongside the road some halfway up the street and very pompous it looked, proud of its distinction as the sole survivor of a belt of trees that once stood along this part of the street and sheltered passers-by. There is no rusticity about the place, yet judging from its name you might expect grassy swards each side of the road, tall hedges with fern and wild flower lurking underneath, and trees of all sorts overhead, sending out their willowy branches, a mass of foliage in summer-time. But it is a green street only in name and very similar in style to many places that line. Watling Street, the great Roman highway that leads from the coast of Kent to London.

THE traveller when passing through Greenstreet will be led to think that it lies in a country far from picturesque. Certainly it is a long, closely-packed street, possessing buildings neither fronted with bright gardens nor sheltered by spreading trees. No; this is not quite fair, for I noticed one tall tree growing alongside the road some halfway up the street and very pompous it looked, proud of its distinction as the sole survivor of a belt of trees that once stood along this part of the street and sheltered passers-by. There is no rusticity about the place, yet judging from its name you might expect grassy swards each side of the road, tall hedges with fern and wild flower lurking underneath, and trees of all sorts overhead, sending out their willowy branches, a mass of foliage in summer-time. But it is a green street only in name and very similar in style to many places that line. Watling Street, the great Roman highway that leads from the coast of Kent to London.

Out of the street is a road that leads to Teynham proper and of which Greenstreet is but an adjunct; and this brings us to the interesting fact that as a parish Greenstreet does not exist and never has existed, for the middle of the road is actually the boundary line between parishes, the land and houses on the north side belonging to Teynham and those on the south side to Lynsted.

Greenstreet as it appears to the traveller is somewhat remarkable for the absence of large buildings, either of a private or business character, but you will very seldom find such varied types-redbrick, yellow-brick, some with tiled and others with plastered fronts, and here and there weather-boarded. At one spot there is a thatched [32] roof surmounting a red-brick house, and as we approach the place from the direction of Faversham we find a timber-framed house some three hundred years old, with buff-coloured plaster as a filling. This is Whitehall and was originally owned and occupied by one of the leading families in the district. Until recently it was surmounted by a thatch roof. The timbered frame was built on a brick foundation. Further along is the traditional village smithy with an old building behind it—a house with many roofs at odd angles and as undulating as the waves of the sea. As your eyes wander along the street here and there you find a block of houses, low-pitched and with overhanging upper storeys now encased in boarding or plastered over. The timber of the wooden frame can be detected in some cases. One of these ranges of buildings possesses windows of the old bay type very popular a hundred years ago.

There appears to be no important residential part of the street, shops being intermixed with private houses, some of which are built flush with the footpath and others recessed. A break in the row of houses on one side of the road is caused by a timber yard and a bright touch of colour is to be found in the signs of the Fox Inn, the George, the Swan and the Dover Castle. We are told in big letters that the Dover Castle stands exactly halfway between Canterbury and Rochester. Far beyond, at the other end, stands a cluster of oasthouses to remind us of one of the industries of this part of the world.

Public buildings are of a modest description and fail to stand out with distinctiveness. At the east end of the street stands a red-brick building now used as a chapel of ease to the parish church of Teynham which stands a mile north of Greenstreet, and those who wish to attend its services must needs pass across bleak and open country. It was a local benefactor, Mr. James Lake, who resided at Newlands, who conceived the idea of providing services for the population residing at Greenstreet, and he presented this building in 1881. According to a brass plate within the chapel he called it a Mission Chapel, and, in addition to handing over the building, invested £300, the interest of which was to be devoted to assisting poor people. Another brass on the wall was erected to the memory of Dr. G. F. Pritchard by two hundred and fifty of his patients, while £56 was collected and invested for the benefit of the poor. The worthy doctor died in 1887 at the early age of [33] forty-seven. The interior of the chapel is bright and plain in regard to ornamentation. The walls are white, relieved by a deep blue dado, but an impressive effect is created by the heavy timbering of the roof at the chancel end, the brackets that support the cross-beams being supported by stone corbels carved with a floral design. Then there is the Wesleyan Chapel, a red-brick building with a cement front and bearing the date of 1841. The Salvation Army, the Red Triangle Club and the St. John Ambulance all possess headquarters of a modest character. The only other public building is the Queen Victoria Jubilee drinking fountain with the following inscription :- " To the worship of God and in loyalty to the Throne, this memorial was set up with offerings from the parish of Teynham and Lynstead in the year of the Queen's Diamond Jubilee."

Such is Greenstreet to-day, but it stands in the very heart of a country that became famous years ago and known as the " Cherry Garden and Apple Orchard of England." It happened in this way. One Richard Harrys, Fruiterer to King Henry the Eighth, conceived the idea that the land hereabouts would be distinctly suitable for the cultivation of the cherry, and he planted several acres with young trees. The result was startling. So luscious was the fruit produced that henceforth this part of Kent supplied the country with the best of cherries, and the imported ones from the Continent—almost the sole supply up to that time—had to take second place.

It should not be thought, however, that cherries had not previously been grown in England, for Pliny tells us that the Romans first brought them to Britain in very early days. But they were cultivated on unsuitable land and could in no wise compete in flavour with cherries produced across the Channel. Later on the Normans brought a fresh supply, but here again the soil in which they were planted- must have been unsuitable, for, according to Lambarde, they deteriorated to such an extent that but for the timely action of Richard Harrys the stock would have died out. The manner in which King Henry's Fruiterer—the royal tradesman in those days was entitled to a capital letter—turned this part of Kent into the Garden of England is related by the Kent historian, Lambarde.

Writing on the same subject a hundred and thirty years ago Hasted says that nearly all the orchards had been displaced by hops, but, he adds, "hops are soon likely to give place to fruit trees [34] again, owing to the little profit of late years accruing from them." Hasted was right. Hops are grown on either side of Greenstreet, but the vast acreage of orchards shows that fruit growing is the staple industry of this part of Kent to-day.

And so I come to the end of a description of a spot which is neither a parish nor town nor village, and yet, if we may judge by the yellow signs of the Automobile Association at each end, it becomes dignified with a name and is apparently more important than the historic villages on either side, and to each of which it contributes a large slice of land and many houses.

Finally, why is it called Greenstreet? The explanation is simple enough. During the reign of Henry the Eighth there lived in this locality a knight by the name of Sir John Norton, and to his paramour was born a son who was outwardly known as Thomas Norton, but by law as Thomas Green. Thus started the family of Greens, who owned much land in Teynham, Lynsted, Tong and Bapchild, and it is assumed that Greenstreet owed its name to this family.

Many years ago a live-stock fair was held on May 1st in Greenstreet, but it was discontinued some time since. It must have been an important affair, for we are told that from one end of the street to the other stood cattle, sheep and pigs collected from a radius of many miles. At one of these fairs " Mr. Thorne's pigman for a wager drank six half-pints of beer in one minute and asked for a seventh "—a performance recorded in the Sporting Chronicle in 1777.

Many years ago a live-stock fair was held on May 1st in Greenstreet, but it was discontinued some time since. It must have been an important affair, for we are told that from one end of the street to the other stood cattle, sheep and pigs collected from a radius of many miles. At one of these fairs " Mr. Thorne's pigman for a wager drank six half-pints of beer in one minute and asked for a seventh "—a performance recorded in the Sporting Chronicle in 1777.

TEYNHAM

PLACES attain notoriety for many reasons, some of a complimentary character, some otherwise. In the case of Teynham we find it can boast of being praised and condemned alike in the annals of our county, for while on the one hand it became part of that bit of Kent known as the Cherry Garden of England—a delightful name—on the other hand it was linked up with two adjacent parishes in the following unsavoury couplet :—

PLACES attain notoriety for many reasons, some of a complimentary character, some otherwise. In the case of Teynham we find it can boast of being praised and condemned alike in the annals of our county, for while on the one hand it became part of that bit of Kent known as the Cherry Garden of England—a delightful name—on the other hand it was linked up with two adjacent parishes in the following unsavoury couplet :—

HE THAT WILL NOT LIVE LONG

LET HIM DWELL AT MURSTON, TENHAM OR TONG.

It will be noticed that in this doggerel, written no less than three hundred years ago, the name of the village is spelt without the letter "y," and it is only of quite recent years that it became Teynham.

It was the swampy part of the parish which made it unhealthy, and anyone who wanders in the meadows that lie between the church and the Swale will realise what a nest of poisonous insect life this must have been before the land was drained. Graveney marshes and Romney marshes were in the same plight years ago, and the inhabitants were subject to marsh ague and other distressing zymotic diseases. Now-a-days irrigation has turned the swamps into rich pastures, and the Swale Level and Luddenham Marshes have in their turn become valuable and healthy land.

But let us trace the origin of Teynham's fame as a fruit-growing centre. It will be remembered that King Henry the Eighth married a Dutch lady, Anne of Cleves, coarsely christened "The Flanders Mare," to whom he took a dislike on his bridal night and subsequently [36] divorced her. But, notwithstanding this antipathy, he was interested in an idea fostered by his fruiterer, one Richard Harrys, to introduce the culture of Flemish cherry and apple into England, and in the course of a few years vast orchards spread over the district and have continued to beautify and enrich Kent ever since.

But I cannot do better than quote the historian Lambarde, who, writing in the year 1570, introduces the subject with quaint references to Kent as a whole. He writes :—

"I would begin with the antiquities of this place, as commonly I doe in others, were it not that the latter and present estate thereof far passeth any that hath beene before it. 'For here have wee, not only the most dainty piece of all our Shyre, but such a Singularitie as the whole British Hand is not able to patterne. The Ile of Thanet, and those Easterne parts are the Grayner : the Weald was the Wood : Rumney Marsh is the Medow plot : the Northdownes towards the Thamyfe, be the Cony garthe, or Warreine : and this Teynham with thirty other parishes (lying on each side of this poste way, and extending from Raynham to Blean Wood) bee the Cherrie gardein, and Apple orcharde of Kent. But, as this at Tenham is the parent of all the rest, and from whome they have drawen the good juice of all their pleasant fruite : So it is also the most large, delightsome, and beautifull of them. In which respect you may phantaise that you now see Hesperidum Hortos, if not where Hercules founde the golden apples (which is reckoned for one of his Heroical labours) yet where our honest patriote Richard Harrys (fruiterer to King Henrie the 8), planted by his great coste and rare industrie, the sweete Cherry, the temperate Pipyn, and the golden Renate. For this man, seeing that this Realme (which wanted neither the favour of the sunne, nor the fat of the soile, meete for the making of good apples) was nevertheless served chiefly with that fruit from foreign Regions abroad, by reason that (as Vergil saide) Pomaque degenerant, succos oblita priores: and those plants which our ancestors had brought hither out of Normandie had lost their native verdour, whether you did eate their substance, or drink their juice, which we call Cyder, he (I say) about the yeere of our Lord Christ, 1533, obtained 105 acres of good ground in Tenham, then called the Brennet, which he divided into ten parcels, and with great care, good choice, and no small labour and cost, brought plantes from beyonde the Seas, and furnished this ground with them, so beautifully as [37] they not onely stand in most right line, but seem to be of one taste, shape and fashion, as if they had been drawen thorow one mould, or wrought by one and the same patterne."

To-day nearly all the countryside in this locality is given up to the cultivation of fruit and hops, and in Spring-time white and coral-tinted blossoms, and other shades of colour deep as crimson, form a picture indescribable. And the disconnected village of Teynham stands in the midst of all this glory—a village made out of the north side of thickly-populated Greenstreet, and a cluster of houses near the railway station known as Barrow Green. In addition there is Conyer Quay. As I mentioned in the chapter describing Greenstreet, Teynham reaches and embraces the northern side of the street of Greenstreet, just as Lynsted extends to the southern side of the street.

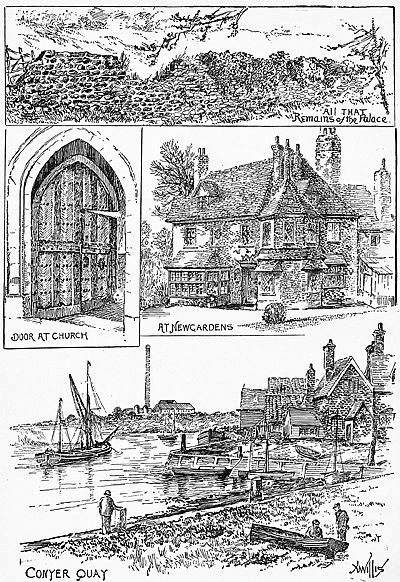

Just before you come to the station you are attracted by a fine brick wall that surrounds Newgardens, which at one time went by the name of Tenham Outlands and was part of the possessions of the Ropers, who subsequently became the Lords Teynham. In 1714, however, Sir Robert Furnese, of Waldershare, purchased the property from the Ropers, and subsequently it came to one of his daughters, the Countess of Rockingham, and it is interesting to read that at that time " the farm consisted of two large barns, two stables, one granary, one lodge, twenty acres of land, arable and pasture, one old cherry orchard and two acres of hop ground." The Countess, after the death of her husband, married the Earl of Guilford, and it remained in the possession of that nobleman's family until Colonel Honeyball purchased it a few years ago.

Colonel Honeyball, during an active life, was one of the most popular men in Kent, being well known as an expert agriculturist and an extensive hop-grower, and commanding officer of a battalion of the East Kent Volunteers, while during his military career he was one of the finest rifle shots in England. Having purchased Newgardens he at once began to restore it and lay out the gardens in an artistic manner. Upon his death in 1923 the property was left to Mrs. Honeyball, and this lady has continued to increase the size of the gardens and enlarge the house. Newgardens is built of red brick, but within can be seen beams supporting the ceilings to indicate that in early days it was a timber-built construction. Up to within a few years ago the residence was covered in ugly plaster, [38] but this was all taken away to reveal some beautiful brickwork of a mellow red tint. A turret at one corner, recently erected by Mrs. Honeyball, is in character with the rest of the building and adds to its impressive appearance. The hall is a spacious apartment, and out of it rises an original Jacobean staircase. In the drawing-room is a beautiful oak mantelpiece also of the Jacobean period, brought from Tonacombe Manor, Cornwall, the home of Mrs. Honeyball previous to her marriage. In an upper room is another charming fireplace, built up from timber taken from the cellars, which, by-the-bye, extend under the whole of the house. There is a remarkable little chamber upstairs leading from one large room to another, probably a hide or powder-room. In many of the windows the ancient lead-lights add a romantic touch to the house, and further evidence of the old style of building can be found in the kitchen department. Here are heavy beams, as well as a large open fireplace. The most interesting feature about the house is that it was probably the residence of Richard Harrys, King Henry the Eighth's Fruiterer, and the first orchard he planted is supposed to be upon this estate. One can picture Bluff King Hal journeying down to Newgardens and enjoying feasts of luscious cherries and apples, and it is in the happy fitness of things that royalty has since then visited the place. The Duke of York accepted an invitation of Colonel and Mrs. Honeyball, and he arrived on July 14th, 1922, to spend a delightful afternoon amid the orchards, while the grounds were decorated with white roses in compliment to the House of York. Previously, on April 21st, 1920, Helena Victoria, daughter of Princess Christian, also honoured Colonel and Mrs. Honeyball with a visit.

The gardens are a feature of this delightful residence. Well-groomed lawns run in all directions, and the other day when I was there—it being Spring-time—thousands of daffodils were peering out of the turf and presenting a gorgeous spectacle with their golden heads thrown up against a green background. In all sorts of odd corners you find enclosures with fountains playing in the centre, and in one corner is a sunken rock garden. One circular enclosure is belted by tall elms, and here the Duke of York was formally welcomed by his host and hostess. Another delightful spot is known as Australia House, a thatched building with tiny dormers peering out of the roof. In the front bricks have been built to represent the sun, the moon and the stars, and facing us are flower beds so [39] planted that in the Spring-time the quiet tone of blue flowers will be indicative of the moonlight, while in the Summer-time, when the sun is in the ascendant, scarlet flowers will give an appropriate brilliant glow. I have never seen bricks treated with such artistic effect as they are in this garden.

Just beyond Newgardens is the station, with a hostelry bearing the appropriate name of the Railway Tavern close by, and a few yards further along a collection of cottages and a school. This is Barrow Green. In the distance stands the church, alone save for the Court Lodge and its farmyard and barns running nearly up to the churchyard wall. A straight footpath through hop gardens leads to the church, but if you must needs ride you have to traverse a winding road, from which you get a glimpse of a farmhouse in the hollow and a row of black cottages that contain workers engaged in the hop gardens close by. The rest of the land is under cultivation for corn and fruit. Two tall trees stand sentinel-like at the entrance of a narrow road that leads to the church.

But if you continue along the winding road you pass a modest little building known as the Wesleyan Chapel and a tumble-down looking house of the Tudor period. The whole of this house was once composed of a timber frame, but patches of brickwork have been inserted with the herring-bone pattern to give them character. One corner, however, retains its original timber and plaster and corner-post, while an oaken Tudor doorway gives admittance to the house. It was once a residence, but is now converted into two dwellings known as Bank's Cottages. A little further on are thatched cottages and a house at the corner which has been encased in some parts in stucco, but one portion discloses the timber which denotes its great age.

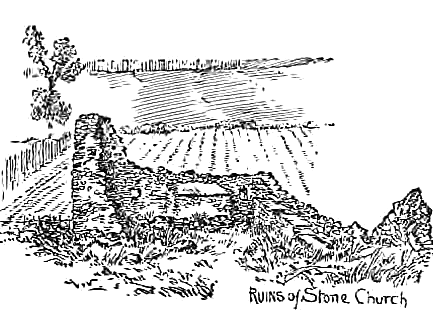

Still further along, opposite some cottages, I came upon the remains of an ancient wall, the material of which is flint. And its thickness is very great. This is probably part of the wall of an outbuilding connected with an ancient archiepiscopal palace which, it is supposed, stood on the present site of an orchard on the left-hand side of the road at the corner where the road leads to Conyer Quay. On the mound grows a large fruit tree. Up to 1847 portions of the ruins were used as farm buildings, but in that year, we are told, "the remaining vestiges were destroyed," but whether by fire [40] or demolition the record does not state. It is, however, quite probable that this bit of old wall down in the marshes, although some distance away, was part of the palace, for such a fine piece of work would only be associated with a place of importance.

A plot of ground near the spot where the palace once stood goes by the name of the Bishops' Garden. It is also interesting to recall the fact that as long ago as the thirteenth century vineyards stood at Teynham and were part of the ecclesiastical estate. Archbishop Walter, described as "the magnificent prelate" owing to the lavish style in which he lived, resided at Teynham Palace and died there in 1205, but was buried at Canterbury. Another Archbishop, John Stratford, during the reign of Edward the Third entertained the Black Prince at this residence, when "great were the festivities."

And where is that old-world bishops' palace to-day? Gone, entirely gone, save for that small bit of flint wall on the edge of the marshes and, as I have said, probably a part of a building which stood some distance from the palace itself. And yet, talking to one who was gardening close by, on the other side of the road to where this old wall stands, he told me that there is a hollow in his garden which can never be filled. Load upon load of soil has been thrown into this hollow, only to be swallowed up. Are there deep cellars beneath? Surely excavations would be worthwhile.

We seem to be at the Back of Beyond while strolling along the pastures down here in the marshes, with their rich grass on which the cattle browse. A rapid stream runs towards the creek, but on either side are the ditches into which superfluous water flows and effects the irrigation that has reclaimed these many acres of land for cultivation. Fruit trees also thrive. Fresh sea breezes redden your cheeks as you stroll about here in this low-lying country, and beyond you see the glistening surface of the Swale and, further away, in the misty distance, the Isle of Sheppey.

The church stands on higher ground and you enter the churchyard through a wooden lych-gate that bears the inscription:—" To the Glorious Dead, 1914-1919." It is worthwhile to walk around the building to see the exceptionally long and well-preserved Early English lancet windows. Other windows are of the Perpendicular period and the large one east of the chancel appears to have been restored. Its slender mullions are elegant. Stone corner buttresses [41] support the chancel, but someone, alas! placed red-brick buttresses against the wall of the south aisle—an unforgivable thing to do. That splash of brickwork amid fine flint and stone! Then there are three little dormer windows of recent date projecting from the roof of the nave—another bit of modernity that mars the beauty of an otherwise fine old Kentish church. Near the lych-gate stands a tall consecration cross, restored on its original base in memory of Captain Gerard Prideaux Selby, R.A.M.C., killed while tending wounded at the capture of Thiepval in 1916. The gallant young officer was only twenty-five years of age and the son of Dr. and Mrs. Selby. Close to the west door are two ancient stone tombs, although the stonework of one has been encased with brick. One bears the date 1617 and the name Pamflett, and at the end is carved a cross.

The church of St. Mary's is built on the cruciform plan, with two extensive transepts and two narrow aisles. The tower is well proportioned in three stages, with embattled parapet and a string course and Perpendicular windows. On the weather-vane is a large cock, painted black. On each side is a lean-to building, one used as a vestry and the other for the stairs that lead to the gallery. These two attached buildings have doorways similar to the one under the tower, while above is a lancet window. The clock in the tower is a memorial to Colonel J. F. Honeyball, who died in 1923, the ceremony of dedication being performed by the Archbishop of Canterbury. The west door has plain mouldings. There is something attractive about the tower -its very ruggedness appeals. The material used is a mixture of stone, flint—large unpolished flint—and rubble, all built in without much precision, while the stone quoins are roughly hewn. Then the two bold buttresses are rugged, too, all tending to show the different style of work carried out by the masons in various parts of Kent centuries ago. A few Roman tiles, probably collected from an earlier building, are inserted in the walls.

Entering by the west doorway you cross the lower chamber of the tower and discover an ancient oak door which can truthfully be described as magnificent. Massive to a wonderful degree, it is also ornate with many iron studs and a cross-piece in the centre with crenellated design. A small door to admit one person is cut out of the door itself. There are several deep indentations which show that it has been hit by bullets. These indentations are large [42] and prove that they were caused by the huge bullet in use when firearms first appeared. It is known that a furious battle was fought between the Royalists and Cromwellians at a place called Barrow Green, and the probability is that the former, utterly routed as we know they were, sought sanctuary within the church, and in their retreat were fired upon by the Roundheads. It is not likely that the latter would deliberately fire at a church door for the mere sake of doing so.

The interior of the church is spacious, high pitched, with a large chancel and two large transepts that are nearly as long as the nave. The tie-beams and king-posts are insignificant in size. The dormer windows, acting as clerestories, seem quite unnecessary, as the whole church is well-lighted. The coved ceilings of the nave and transepts are now plastered over, but it is to be hoped that at no distant date the timbered roof will be exposed to view—a vast improvement in a very fine church. And this brings us to the question: Why was such a large building erected here? The explanation is that the archbishop's palace once stood at Teynham and it is believed that the country around the church was very thickly populated centuries ago.

Expansive arches are the feature of the church. Two wide ones divide the nave from the aisles, while the arches leading into the transepts and the chancel arch are also large, but plain in style. Smaller arches divide the aisles from the nave. By the side of the chancel arch, which springs from octagonal half pieces are the doorways leading to the rood-loft. There are two strips of oak on each side of the entrance to the chancel, and one of them is said to be part of the ancient screen that was taken down at the time of the Reformation. The Communion table is a fine specimen of seventeenth-century oak carving, and the pulpit, also of that period, is ornamented with a design of great delicacy.

Those old treasures of the church remind us of the days when the place must have borne a quite different appearance. The chancel floor was lower than the nave, but to-day we rise by two steps to enter it. The transepts no doubt contained altars in their eastern walls, and there is abundant evidence that plain plaster has been used to fill up various openings and to leave merely bare walls. On one of the north transept walls are the remains of a fresco, [43] discovered under the plaster a short time ago, and there is but little doubt that if other parts of the church could be denuded of plaster various objects of interest would be found. Among other things some ancient stained glass has disappeared and all that remains of it is a collection of fragments placed together indiscriminately in one of the north transept windows. Yet a hundred years ago Teynham church prided itself upon its old coloured windows. Hasted tells us that several of the windows had rich Gothic canopies of beautiful coloured glass, under which there were figures of equal beauty. In a south window of the chancel was the figure of a girl in blue, kneeling and pointing to a book, which was held by a man who likewise pointed his hand towards it. In the north transept were two windows, one of which contained an episcopal figure with a mitre, while in a window of the vestry was another piece of stained glass illustrating a mitre. Parsons, in his " Monuments of Kent," gives a more detailed description of these fine old windows.

At the present time we find many modern coloured windows and it is probable that when they were inserted the pieces of ancient glass were taken away. The large chancel window—a beautiful window both in design and lightly-tinted colouring—contains stained glass to the memory of James Lake, who died in 1881, and the two tall lancets in the north transept are to the memory of Robert Lake, who died in 1911, and one to Sarah Lake, who died in 1865. While the last one is glaring in its over-bright colouring, the Robert Lake lancets are subdued in tone and the most beautiful ones of the church. In the south transept are three lancets to the memory of members of the Dixon family, dating from 1894 to 1900, while in the south aisle is a stained-glass window to the memory of the wife of William Roper Dixon, who died in 1916, and to their son, MacDonald, killed in 1917 during the Great War. Another window is to the memory of William Roper Dixon himself, his death occurring in 1924. In the north aisle is a stained-glass window to the memory of Annie, wife of Richard Dixon, dated 1916, and also their daughter, who died in 1920. In the south transept is a coloured Perpendicular window erected by the vicar and churchwardens in 1903. The two elegant tall lancets, with a little quatre-foiled window high up in the centre, are similar in shape to those in the north transept, and contain stained glass, but there is no record as to whether they are memorial windows or not. [44]

Among other objects of interest in the church are the many Early English lancet and square-headed Perpendicular windows ; two deeply-splayed circular windows in each transept ; a stopped doorway in the north wall ; a stone seat at the end of the north transept ; a piscina in the south wall of the chancel with a bowl not in the centre ; a recess and piscina in the south transept ; a cupboard built in a stone recess of the wall behind the altar ; and a modern font with an octagonal bowl supported by a circular stem ; an oak pulpit beautifully carved and entered by a door which is still hung on old hinges ; and the plain oak screen between nave and chancel. The darkness of this ancient oak is in direct contrast to the light pitch pine of the modern choir stalls. Quite recently an ugly gallery that extended across the nave in the western side was removed and an organ loft erected in its stead, while the high pews were succeeded by the present low ones made of cold-looking pitch pine.

An elegant brass tablet is a War Memorial and contains the following names :—Frederick Back, William Frank Back, Arthur William Beesley, Benjamin Dan Black, Ernest Black, Henry Thomas Carvier, Stephen Champ, Frederick George Champ, Ernest Cheesman, Fergus William Christmas, John Dalton, Daniel Edward Eason, Alfred Henry Fearer, William Ford, Joseph Henry Ray, Reuben Reader, Ernest Ridley, Frank Russell, Gerard Prideaux Selby, Henry Smith, George Thomas Swan, Cornelius William Taylor, Leonard Terry, Albert Tumber, Edward James Wictor White, Thomas Wigg. On a small tablet underneath are further names :—Thomas Baker, John Henry Gladwell, Albert Edward Hadlow, George Abraham Hall, Charles Edward Higgins, William Henry Hodge, Thomas Warwick Kite, James Frederick Laker, William Henry Laker, James Lucas, William McGarry, Sidney Philpot, William John Pile, Percy Wildish, George Potts, Bertie Charles Downs.

Four ancient brasses are in splendid condition. The largest one is on the floor of the chancel and represents William Palmer and Elizabeth, his wife, each in the act of prayer, while the family coat-of-arms is on a shield overhead. A marginal inscription reads :¬" Here lyeth buryed the Body of William Palmer, the sonne of ' William Palmer of Horndon in the County of Essex, gent. who departed this life the 3rd of June in ye yeare of Our Lord God, 1639." A small brass tablet at the foot of the two standing figures tells us that " Here alsoe lyeth buryed the Body of Elizabeth Palmer, [45] late wife of William Palmer, who departed this life the 27th of February, 1639." He is in civil dress with ruff and cloak ; she in long veil, ruff, bodice and gown. In the south transept, placed on a slab and lacking its original matrix, is a brass representing a man in plate-armour wearing an S.S. collar—John Frogenhall. A dog is at his feet. Unfortunately, the inscription is missing, but the words are preserved in the collection of the Society of Antiquaries. On the floor of the north transept, also fixed outside a slab and minus a matrix, is an effigy representing a civilian, and the inscription states that he is Robert Keyward, who died in 1509. With him are buried his father and mother. Under the inscription are two figures representing their family, one being a grown-up daughter with long hair and the other a child in swaddling clothes. Another brass in this transept represents William ''Wreke, with the date 1533. He, too, is in civilian dress. There are three modern plain plate brasses —one in the wall of the chancel to the Rev. Edward James Corbould, vicar from 1878 to 1908 ; one in the nave to James 'Frederick Honeyball, of Newgardens, who died in 1923 ; and the third in the south transept to Samuel Creed Fairman, who died in 1858, and his wife Christian, who died in 1873. The latter was a daughter of General Gosselin, of Mount Ospringe. Both lie buried in the transept.