Tudor Cottage, Cellar Hill (off Greenstreet)

- "Period Home" Article by Dr Robert Baxter

- Restoration Process and Other Images

- Kent Historical Environment Record (HER)

- Royal Commission on the Historic Monuments of England - 1986 & 1992

- Society visit to Tudor Cottage - 31st July 2011 - Report

Article Originally published in 1985 in "Period Home" (now deleted)

Author: Bob Baxter, the current owner

"IT has been truly said that these old buildings do not belong to us only: that they belonged to our forefathers and they will belong to our descendants unless we play them false. They are not in any sense our property, to do as we like with them. We are only trustees for those that come after us."

William Morris, 1877

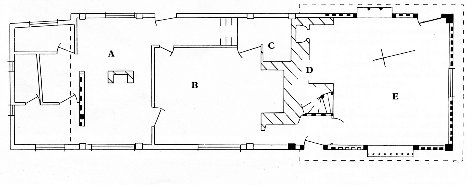

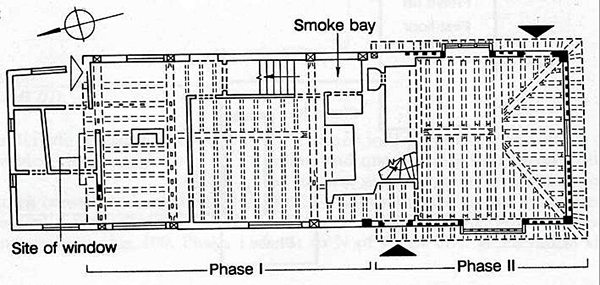

TUDOR Cottage, previously 17/19 Cellar Hill, is one of the three ancient timber- framed dwellings that survive along Cellar Hill Lane which runs south from the main London to Canterbury road (A2) at Teynham (strictly, Greenstreet) following the west rim of a 'dry valley' that stretches northward from Lynsted Park. The building is of the hall house type common in this area of Kent. It lies directly against the east side of the lane and with its long axis parallel with it.

The building was associated with the estate of Nouds. No deeds or other documents have yet come to light. The records of Lynsted parish contain no obvious reference to the dwelling or its occupants.

The house is 19 metres long and 6 metres wide. It has essentially a four-bay plan. The south end has been rebuilt, probably within a few decades of the date of construction of the original house. This newer bay (or double bay) is jettied on all three external sides. The north end has been overshot to provide additional space on the ground floor.

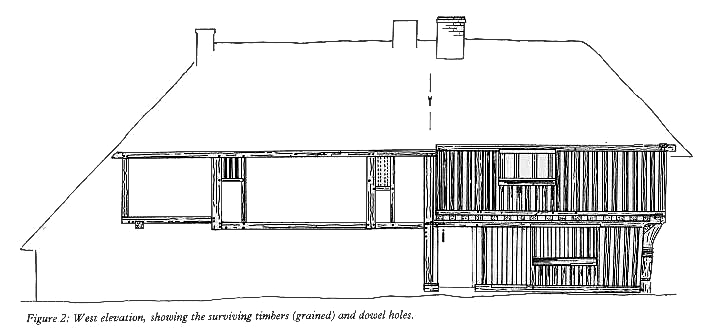

Very little of the original wall timber, and none of the in-fill, survives on the ground floor. These walls now consist of brick underpinning. Where the brickwork is exposed and not rendered over, Flemish bonding is revealed. Hence this brickwork is later (probably much later) than mid-seventeenth century. Much of the oak timberwork of the upper storey and roof survives, as do several windows, plaster and wattle-and-daub.

The suite of small rooms at the north end, under the overshot, is certainly recent. Local residents remember this area being used for stabling a horse.

The Five Bays

Figure 1 - Bay A

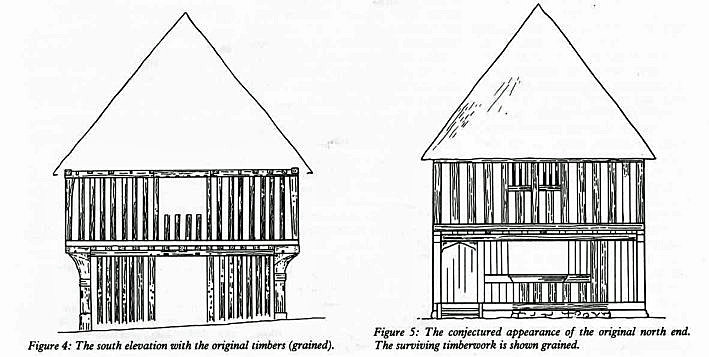

Certain timbers of the original north end of the house are clearly visible. A section of the north wall cill-beam survives, as does the girder. The latter exhibits, at its east end, much chisel-work on the under surface. This was evidently to accommodate the spandrel hood of a substantial door. Mortices for the door jambs can be seen. Also on the under surface of this beam is a long shutter-groove. Between this beam and the cill-beam, and supported by stout studs, is what appears to be a massive window till. This cill bears the remains of elaborate moulding on its outer surface. There is a shutter-groove on the upper surface of this window cill that corresponds to that in the girder above. There is, however, no sign of the diamond-section window mullions that occur elsewhere in the house. The most probable explanation is that this served as a shop window. Entry to the shop would have been by way of the door alongside the window (Fig 5)

|

|

|

Conjectured appearance of the house when built (about 1520), as viewed from the east. Note the absence of chimneys: the fire and smoke were confined to the narrow "smoke bay" towards the south end. The southernmost bay was replaced a few years later.

Elevations of Tudor Cottage

The presence of a row of mortice holes in one of the ceiling joists indicates that a stud-partition separated the shop itself from this entrance-doorway. There are no mortice-slots at the east end of the stop-chamfered cross-beam that 16 marks the division between the first and second bays. Thus it would have been possible to pass directly from the north entrance to the second bay without entering the shop. It was possible to enter the shop from the inner end of the entrance-passage. Apart from the gap left at the north door passage, the first and second bays were separated by a stud partition.

The ground floor of the first bay was ceiled over with oak joists that extended over the girder beam to form a jetty at the north end. All but two of these joists have been replaced.

The north wall of the upper storey is in a remarkably good state of preservation. This could have been due to the presence for much of the life of the building of some form of overshoot. (The existing rafters of the overshoot are modern.) The studding is close, and much of the wattle-and-daub is still in place. A pair of centrally-positioned windows survive (Fig 5). Five of the six original diamond-section mullions are in place, and shutter grooves are evident. Modern wall thickening precludes study of the wall-plates and it is not possible to say if windows existed at the east and west sides. The arrangement of studs and rails would, however, allow for such windows. Rectangular-paned cast iron casement windows have been inserted in the east wall of the first and second bays.

In all, the heavily timbered aspect of the north side of the house contrasts with the sparser woodwork and large panels of the east and west elevations. Perhaps this reflected a desire of the owner to impress visitors (customers?) approaching from the main thoroughfare to the north.

The tie beam at the border of the first bay is chamfered on the first bay side only. This indicates that the second bay was an area of secondary importance such as a store area.

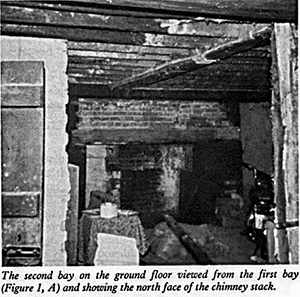

The Second Bay - B

The second bay is larger than the first. A large bridging beam, with chamfers, bisects the lower floor ceiling. It is likely therefore, that this lower floor room was ceiled from the beginning and not open to the roof as in the traditional Wealden hall house. The original joists have been replaced by softwood timbers. Part of a second bridging beam, parallel to the central one, is visible where it joins the cross beam at the south-east corner of the room. It is possible that the space between this minor bridging beam and the east wall was meant to take a ladder or stair leading to the upper floor. A recent stair now occupies the space.

The second bay is larger than the first. A large bridging beam, with chamfers, bisects the lower floor ceiling. It is likely therefore, that this lower floor room was ceiled from the beginning and not open to the roof as in the traditional Wealden hall house. The original joists have been replaced by softwood timbers. Part of a second bridging beam, parallel to the central one, is visible where it joins the cross beam at the south-east corner of the room. It is possible that the space between this minor bridging beam and the east wall was meant to take a ladder or stair leading to the upper floor. A recent stair now occupies the space.

Dowel-holes in the girding beam on the east side indicate that there was a simple door where the present back door is now hung. It is likely that there was a corresponding door in the west wall. One dowel hole, that could have held the peg to secure a jamb, is visible in the western girding beam. A doorway existed in this position as recently as 1951. The existing brickwork shows the signs of blocking up, and the remains of a step are to be seen at the foot of the wall. This door was likely to have been built in the position of a previous door. The 'opposite' arrangement of side doors is common in timber-framed buildings in Kent. They were originally associated with cross-screens at the 'lower' end of a house. The position of the pair of opposite doors in this house indicates that the south was the 'upper' and the north the 'lower' end of the original building.

Dowel-holes in the girding beam on the east side indicate that there was a simple door where the present back door is now hung. It is likely that there was a corresponding door in the west wall. One dowel hole, that could have held the peg to secure a jamb, is visible in the western girding beam. A doorway existed in this position as recently as 1951. The existing brickwork shows the signs of blocking up, and the remains of a step are to be seen at the foot of the wall. This door was likely to have been built in the position of a previous door. The 'opposite' arrangement of side doors is common in timber-framed buildings in Kent. They were originally associated with cross-screens at the 'lower' end of a house. The position of the pair of opposite doors in this house indicates that the south was the 'upper' and the north the 'lower' end of the original building.

The upper floor of the second bay was probably open to the rafters. There is no evidence for ceiling joists or bridge beams. It seems that, for at least part of its existence, the room was continuous with that of the first bay. The carpentry in this second bay (simple doors and windows, edge-halved scarf joints in wall-plates, heavy braces) is in the style of a yeoman's house of the latter part of the sixteenth century.

The Third Bay - C

The third bay was almost certainly a smoke-bay. The eastern two-thirds of the cross beam that separates the second from the third bay is deeply chamfered on the third bay side. This could have been a device to help guide smoke upward from a fire on the floor of the third bay. Toward the west end of this cross beam, there is a mortice slot and dowel hole that must have secured a substantial upright. This could well have been part of the support for a partition that screened off the fireplace and allowed access from the second bay to the southern part of the house. Spaced mortice-holes along the entire length of the tie beam of the upper storey show that the second bay room upstairs was completely sealed off from the third bay. Thus the through-passage was not repeated on the upper floor.

There were upper storey windows at both sides of the bay and these have survived. Windows in smoke-bays are not uncommon: presumably they helped to disperse the smoke.

The conclusion is that a third bay hearth and smoke-bay were there from the beginning. There was never a central hearth in the 'hall' (second bay) as might have been expected in an earlier building.

A massive brick fireplace and stack, dating from the eighteenth or nineteenth century, now occupies the hearth area. A reused beam serves as a mantel. On the upper floor an additional flue serves a nineteenth century basket fireplace. No doubt this fire provided warmth for a Victorian 'drawing room' in the upstairs second bay.

The Fourth Bay - D

The whole of the south third of the house is of a more richly timbered style than most of the rest. Only the original north aspect bears comparison. The change in floor level at the fourth bay and the discontinuity in roof construction of the third and fourth bays strongly suggests that the southern end of the original house was demolished and rebuilt in a more ornate style. It is possible that the south end was destroyed by fire; the wooden framework of the smoke-bay must have been prone to this danger.

It seems that the rebuilding provided a chance to incorporate a large chimney stack and fireplace within the fourth bay. Alongside this chimney a spiral stair was built, providing a second access to the upper floor. The treads of the stair are of oak, with ancient brick infill. The brickwork within the fireplace has been refaced at various times, but the main structure was probably inserted soon after 1600.

In recent years an external door has been inserted in the west wall. This was moved from a position next to the west window of the fifth bay some time after 1951. However, dowel holes in the beam above indicate that the original position of the door is that which it now occupies. This would be consistent with traditional building layouts.

The upper storey of the fourth bay shows evidence of truncated wall plates and adjustments to incorporate the jettied fifth bay. A fireplace with a chamfered, four-centred-arched oak mantel was inserted in the chimney at first floor level. This was presumably the source of warmth for the single large room in the upper fifth bay. A Victorian cast-iron grate was incorporated at a later date.

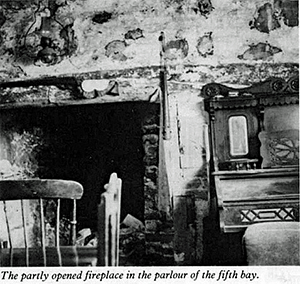

The Fifth Bay - E

Tudor FireplaceThe fifth bay (really a double bay) has evidently replaced what was probably the fifth and last bay of the original house. The newer portion is considerably more ornate than the structure it replaced. Both storeys retain most of their close-studding. On the west, and on part of the east walls, the cills are still in place. There were projecting windows on each of the external walls of the single downstairs room (parlour). Those on the east and west retain some of their original moulded mullions. Clearly, they were intended to be glazed. The cills of the windows are of heavy, moulded oak. Some of the studs are shaped to project slightly to help support the cill-beam. All three windows have shutter grooves in the timbers above them. The south window has been replaced, but the 'brackets' carved in the studs and the pairs of dowel-holes that would have held pegs for a heavy cill, show that it was similar to the other two.

Tudor FireplaceThe fifth bay (really a double bay) has evidently replaced what was probably the fifth and last bay of the original house. The newer portion is considerably more ornate than the structure it replaced. Both storeys retain most of their close-studding. On the west, and on part of the east walls, the cills are still in place. There were projecting windows on each of the external walls of the single downstairs room (parlour). Those on the east and west retain some of their original moulded mullions. Clearly, they were intended to be glazed. The cills of the windows are of heavy, moulded oak. Some of the studs are shaped to project slightly to help support the cill-beam. All three windows have shutter grooves in the timbers above them. The south window has been replaced, but the 'brackets' carved in the studs and the pairs of dowel-holes that would have held pegs for a heavy cill, show that it was similar to the other two.

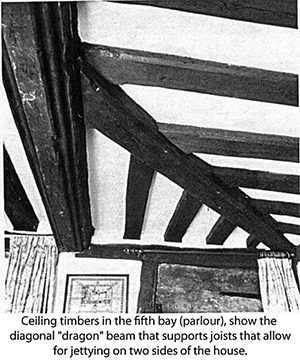

The lower room is ceiled with heavy oak joists with stopped-chamfers. These project to form a jetty on all three external sides. A moulded beam of massive dimensions spans the room. Dragon beams run from the centre of the main beam to the corners of the house, where they are supported by teasel-posts. These posts display a band of carved decoration and some large mortice-slots. The latter may have been to take rails of a fence or enclosing device of some kind.

The lower room is ceiled with heavy oak joists with stopped-chamfers. These project to form a jetty on all three external sides. A moulded beam of massive dimensions spans the room. Dragon beams run from the centre of the main beam to the corners of the house, where they are supported by teasel-posts. These posts display a band of carved decoration and some large mortice-slots. The latter may have been to take rails of a fence or enclosing device of some kind.

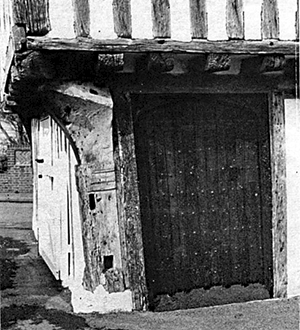

On the west wall, an unusual position next to the corner teasel-post, is a large and ancient door. This has a four-centred hood and carved floral decoration in the spandrels. The jambs are moulded. The horizontal inner timbers, as well as the upper part of the outer woodwork of the door appear to be original. The hinges could also be the original fittings.

The upper area was also illuminated by three projecting windows. The east and west windows retain their heavy, unmoulded cills and lintels. The east window shows evidence of having at one time held leaded lights. The south window has been replaced, although rectangular mortice holes for six mullions can be seen in the lintel. In the rebuilt arrangement, this upper room would have been reached from the parlour via the newel stair.

The Roof

The roof is of sans-purlin type, with paired rafters. It is in two distinct sections, and this is further evidence for the rebuilding of the south end. Each pair of rafters has, or had, a collar. The collars are lapped. In the north half these joints are dovetailed. Those in the south part are straight. At the point of division of the first and second bays, the rafters have an additional short collar near the roof apex. The gablet thus formed is larger than that at the corresponding point at the south end.

The construction can be described as being of the Single-Rafter, Type 1d category. (*see endnote)

At the junction of the second and third bays, the triangular area formed by the rafters and the collar is blocked with (chestnut?) withies woven to form a base for plaster. Much of the plaster survives, and is blackened by soot. There can be little doubt that this is a remnant of the north side of a smoke-bay. The rafters that would have run within the smoke-bay, although since cleaned and woodstained, show evidence of smoke blackening.

At least two of the rafters within the third (smoke) bay have seatings for secondary collars. One of these collars may have been part of the south-end gablet of the original building.

There are no seatings for any collars on the two rafters that lie where the oldest (parlour) chimney passes through the roof. This shows that this portion of the roof was built after (and around) the chimney. The chimney was built to one side of the centre line of the roof. The rafters to the east are therefore truncated. In contrast, the more recent chimney just to the north thrusts through and past the heat-warped rafters. At least one of the rafters has been removed to make way for the stack. Between the pair of chimneys, and morticed into the centre point of the tie-beam that divides the fourth from the fifth bay, is a simple crown post. One of the pair of 'down braces' survives. The tenon for the joint to the collar is to be seen at the upper end of the rectangular post.

The collars in the newer southern part of the roof have at some stage been removed. This, together with the weakening caused by chimney-building at the join of the two sections, may have been responsible for a degree of racking in the structure.

There are no crown posts to be seen in other parts of the roof. Recent plasterwork could hide at least two more, however.

Conclusion

One explanation of the evolution of the dwelling that is consistent with the structural evidence is as follows:

In the latter part of the sixteenth century a small merchant or trader decided to build a house in the parish of Lynsted. It is possible that the merchant was involved with the wool trade. This had emerged as a major national industry at that time. The merchant chose his plot hard by one of the tracks (a legacy from Roman times) that ran at right angles from the main London to Canterbury road. The building was of the simple, sturdy timber-frame construction, and comprised four bays. The style was broadly that of a yeoman's house of the time in this area. Traditional features included the large wattle-and-daub-filled panels, unglazed, diamond-mullioned windows, and a pair of doors set opposite each other in the east and west walls.

In this house, however, concessions were made to accommodate the needs of a man of business. The north frontage was close-studded in opulent style to impress potential customers (and pilgrims?) approaching from nearby Watling Street. A large shop-window was incorporated. So was an extra rather elaborate door for the convenience of favoured clients.

At the end of the day, one could imagine the patron sliding the heavy shutter across the shop window and retreating to his main 'hall' at the centre of the house. This large room would have been warmed by a fire on the floor of the adjoining smoke-bay. The merchant had had this main 'living' room ceiled after the modern fashion. This provided a spacious area for storing his stock, bolts of woollen cloth, perhaps, at the top of a flight of stairs at the east side of the 'hall'. At bedtime he would walk along the passage beside the smoke-bay to retire to his bedchamber at the south end of the house.

Some time alter the erection of the house, and possibly within the lifetime of the builder, a major event took place. Disaster struck. Smoke-bays, constructed as they were of plaster-covered wood, were constantly at risk from the fires they contained. One day, probably in winter, the flames leapt too high. The heat-dried wood framework caught fire. The wind was from the north on that day, and the flames roared southward, destroying the end bay but leaving the bulk of the house unharmed.

As only a small proportion of the building was damaged, it was reasonable to build a new section attached to the surviving structure. The owner took the opportunity to use the new materials and techniques that had arrived with the onset of the seventeenth century. The merchant, or his descendant, had evidently become more well-to-do. The new south end was larger and more richly ornamented than the structure it replaced.

The close-studded walls were penetrated on all three sides by large, glazed oriel windows. Gone was the prejudice against windows in south-facing walls: the enlightened view was that the south wind was not responsible for carrying plague into a house! The windows on the ground floor sported moulded cills. At least one of the upper storey windows was fitted with leaded lights.

The new 'extension' was jettied on all three outer sides, the overhang being supported by richly moulded cross beam, dragon beams and teasel-posts. The spacious parlour was warmed by a fire safely enclosed in a specially-built fireplace and stack of fashionable brick.

The opportunity was taken to insert a spiral stair beside the fireplace. Two doors were included in the new layout: one was positioned opposite the stair. The other, decorated with carved spandrels, was fitted in an unusual position at the extreme end of the east wall, adjacent to the teasel-post.

The higher degree of elaboration did not extend to the roof, however. Despite the inherent tendency for the structure to 'rack' for want of longitudinal support, the idea of using paired scantlings with no collar-purlin was retained. The collar construction was simpler (and weaker) than that of the older part of the house.

The junction of the new with the old part of the house involved changes in floor level. Iron straps were fitted to girder beams to help keep the two parts together. Despite this precaution, a certain amount of distortion took place subsequently.

Some time later, possibly in the latter part of the seventeenth century, plaster ceilings were inserted in the upper rooms at the south end. At some point the collars were removed from the south-section roof. The roof at the north end was extended to provide more living space under the overshot. The dwelling eventually came under the ownership of the Nouds estate. In the nineteenth century cast iron casement windows were inserted at the north end of the house, on the east side. It seems that one of the landlords was of the 'improving' kind!

A further modification, probably also made in the nineteenth century, was the provision of a cellar. This brick-lined cavity still exists.

In the course of time the building was divided into several separate dwellings through the provision of various partitions. The door in the west wall of the south bay was moved. The south walls were weather-boarded. Various outbuildings were added against the east wall. In the 1950s the roof was thatched with straw.

In 1968 the building was purchased from the local council, restored and converted back to a single dwelling and rethatched in Norfolk reed.

Photos by Peter J. Greenhalf.

Footnote: *Cordingley, R. A., British historical roof-types and their members: a classification. Proceedings, Ancient Monuments Society, 9:73-118, (1961)

Restoration Process and other images

|

The building as two dwellings in 1951, taken from the south west. Note the cladding on the south end, and position of the front door. |

|

In the winter of 1987 |

|

Tudor Cottage South-west Aspect |

|

Tudor Cottage from the North West. |

|

Mabel Sherwood in front of her Cottage (no longer standing) opposite Tudor Cottage in Cellar Hill |

Kent Historical Environment Record (HER)

HER Number: TQ 96 SE 1080

Grade II listed building. Main construction periods 1500 to 1599

Summary from record TQ 96 SE 45: This listed house on Cellar Hill, Lynsted, was constructed between 1513 and 1533.

Grid Reference: TQ 95516 62156

SITE (Medieval to Post Medieval - 1500 AD to 1599 AD)

TQ 96 SE LYNSTED CELLAR HILL (east side)

3/39 Tudor Cottage (formerly listed as 2 cottages, 27.8.52 occupiers Hanford and Streatfield). GV II

House, sometime 2 cottages. C16. Timber framed, part underbuilt with painted brick and plastered first floor, part exposed and close-studded with plaster infill, with thatched roof. Five framed bays. Two storeys, with continuous jetty to right on dragon posts and returned on right front. Hipped roof with central stacks. Four wood casements and 1 oriel to right on moulded projecting cill on first floor, and 3 wood casements and 1 oriel to right with 8 mullioned lights on ground floor. Central boarded door with four centred arched surround.

Listing NGR: TQ9555261706

Dendrochronology dating gave a date range of 1513-1517. (2)

Dendrochronology dating of the parlour addition gave a date range of 1518-1553. (3)

English Heritage, List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest (Scheduling record)<2> Vernacular Architecture Group, ADS Dendrochronology Database (Website)

<3> Vernacular Architecture Group, ADS Dendrochronology Database (Website)

Cross-ref. Source description

--- Scheduling record: English Heritage. List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest.

<2> Website: Vernacular Architecture Group. ADS Dendrochronology Database. Vol. 20, Pg. 42.

<3> Website: Vernacular Architecture Group. ADS Dendrochronology Database. Vol. 19, Pg. 48.

Royal Commission on the Historic Monuments of England between 1986 and 1992: Tudor Cottage (Cellar Hill) References

Building structural history details were explained following a survey carried out by the Royal Commission on the Historic Monuments of England between 1986 and 1992:

House of 2 early 16th-century phases, both of which present problems of interpretation.

- 1st phase is hall and upper end of smoke-bay house;

- 2nd phase is elaborate parlour.

Phase I (1514)-1520*. Timber. Floored hall and jettied upper end. Hall heated by smoke bay to S. Former lower end was contemporary, as indicated by pegs for rails on posts at rear of smoke bay, and by projecting sill. Position of main entrances unknown - could have lain in demolished lower end. At ground-floor level, smoke bay did not extend right across to front wall; the passage between smoke bay and front of house is floored, but there does not appear to have been any way through closed trusses from chamber over hall or chamber over lower end: the 1st floor could have been a smoking chamber only reached from within smoke bay. Upper end to N has unusual plan: end bay was entered from hall by doorway in normal position beside rear wall, but it did not lead directly into the main room - instead, main room was entered from a passage which lay beside rear wall and led to external doorway in end wall (cf Summerfield Cottage, Woodnesborough); window in end wall had projecting moulded sill. On 1st floor, truss between upper end and hall bays was open, making a large 2-bay chamber. Position of stairs unknown owing to replacement of many joists. Upper-end wall close studded, the rest in large framing. Collar-rafter roof.

Phase II 1518-(1528)-1538*. Timber. Large parlour bay, constructed on site of former lower end, so that Phase I's upper end must have been relegated to service function; jettied on all 3 external sides. Plan appears to have chimney stack backing on to smoke bay, with stairs to its W. Doorway in front wall opened against the stairs, making a lobby entry: although this is scarcely credible at so early a date, there is no evidence that either fireplace or entrance are secondary. Further external doorway at rear, beside end wall. Ground-floor windows in front and rear walls have deep projecting moulded sills. All 3 external walls are close studded. Collar-rafter roof.

Tree-ring dating: 9 samples were taken from joists. All samples dated (VA 23). 55035 (Level 3 IP D)

Figure 1: Tudor Cottage Floor Plan

Heating in early two-storeyed houses

From the beginning of the 16th century, houses were being built which were designed to be of two storeys with enclosed fireplaces. An agreement of 1500 to build a three-cell house in Cranbrook specified that it was to be lofted throughout and heated by a chimney with two fires,10 and although no surviving two-storeyed houses of quite such early date have yet been firmly identified, they certainly survive from a few years later. A number have been dated by tree-ring analysis, and these include Court Lodge, Linton, of c.1506*, Little Harts Heath, Staplehurst, 1507*, Rocks, East Mailing and Larkfield, 1507/8*, Place Farmhouse, Kenardington, 1512/13* and Tudor Cottage, Lynsted, c.1514*. Rocks is unusual and may not have been a normal dwelling, but the others are well-appointed houses which were fully two storeyed from the start. Court Lodge and Place Farmhouse are early continuous jetty houses and seem to have been heated by external lateral stacks in the position suggested above for those late open halls with enclosed fireplaces.

Tudor Cottage mouldingOne of the notable features of the new two-storeyed houses of the early 16th century is that they are among the first to show a marked improvement in the quality of the ground-floor room at the 'upper' end, which was now almost certainly used as a parlour. At Tudor Cottage the parlour ceiling joists received unusual attention for their date, and are the most decorative in the house.

Figure 2: Cross section of parlour ceiling beam, showing relatively elaborate moulding.

Figure 2: Cross section of parlour ceiling beam, showing relatively elaborate moulding.

Open halls (i.e. the earlier form, with no ceiling between the ground floor and the rafters) continued to be built until well into the century, however, one of the windows (upper floor on the north side) still shows the vertical, diamond-section timber mullions that were originally unglazed. The window (from 'wind eye' ) was closed by sliding a wooden shutter-board sideways, from its internal storage position, along grooves cut into timbers above and below.

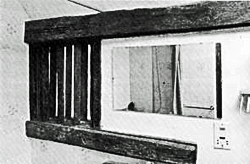

Figure 3: Shutter-board - internal

Figure 3: Shutter-board - internal

The parlour end of Tudor Cottage displays oriel (boxed) windows. These are scarce in houses built before the end of the 16th century. Three of the four surviving examples have elaborately moulded sills.

Figure 4: Oriel parlour window, c.1528, with moulded sill, projecting beyond the main line of the wall.

Figure 4: Oriel parlour window, c.1528, with moulded sill, projecting beyond the main line of the wall.

Acknowledgement. This material is reproduced, with permission, from: A Gazetteer of Mediaeval Houses of Kent, S Pearson, P S Barnwell and AT Adams, 1994; The Mediaeval Houses of Kent: an Historical Analysis, S Pearson, 1994, and The House Within: Interpreting Mediaeval Houses of Kent, P S Barnwell and A T Adams 1994. Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England.

©Crown copyright. NMR . Author: Bob Baxter

Society visit to Tudor Cottage - 31st July 2011

A 'full house' of Society members descended on Tudor Cottage on a fine day that favoured us as we explored the cottage garden or were expertly escorted in two smaller groups by Bob Baxter. This charming 'hall house' is one of the small cluster of remaining thatched mediaeval houses in Cellar Hill.

Our visit began with a short talk about hall-house construction techniques, illustrated with models and simply pointing to the features on the outside of the house.

Very quickly we learned that the Tudor Cottage was a tale of several parts. The main body of the house was significantly added to only a matter of a couple of decades after the original build! Quite why this was so is not known. There are striking differences to the two parts - the older part showing fewer upright oak timbers that mark out the addition as more 'opulent' in terms of ownership. Internal features showed a range of developments, reflecting innovations such as glazed windows (no longer needing slides for boards to make weather-tight!). Between the 'new' and 'old' parts, there sits a section that allowed the smoke from the inglenooks to draw up and out of the building; thus replacing the early feature of hall-houses of an open fire with no chimney but venting out through gaps left for the purpose). Under the long labour of love from the Baxter family to expose original features, we were able to see mysterious echoes of the past in various grooves, mortice holes, and internal layout that includes a large fireplace on one of the first floor landings! There is also a substantial and ornate (for the period) heavy oak door that raised more questions than answers - it faces onto the garden - so did the road pass to the east of the cottage at one time rather than the west? Would an easterly lane imply a change in location for the well? Too many questions!

The Society are fortunate to have been given access to a thorough historical appraisal of Tudor Cottage that can be enjoyed from this web site.

Opening up their home was made even more enjoyable by the home-made cakes and teas laid on by Norma, friends and Committee members and other friends. A thoroughly enjoyable afternoon.

Nigel Heriz-Smith